(Mains2: Issues relating to poverty and hunger)

Context:

- The Global Hunger Index (GHI) rank of India for 2021 is 101 out of 116 countries shows the severity of the hunger problem in India.

- Barring last year’s rank of 94 out of 107 countries, India’s rank has been between 100 and 103 since 2017.

- The government of India has questioned the methodology of the Index and claimed that the ranking does not represent the ground reality.

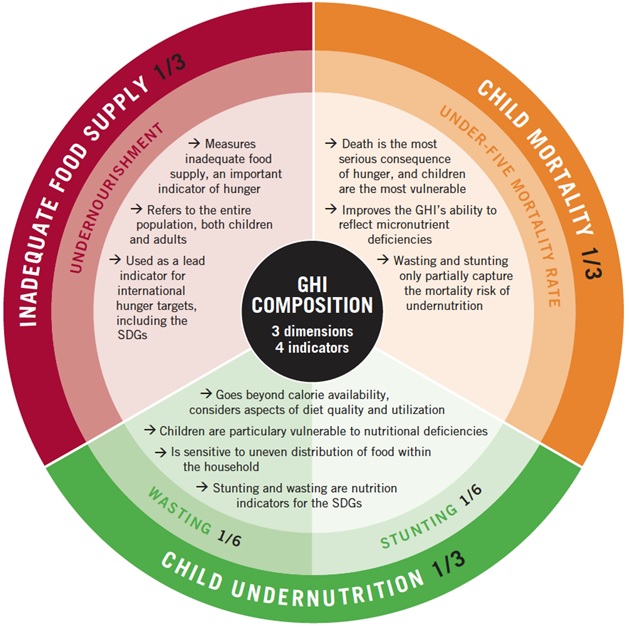

About global hunger index:

- The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a tool designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger at global, regional, and national levels.

- GHI scores are calculated based on the values determined for four indicators:

- UNDERNOURISHMENT: the share of the population that is undernourished (that is, whose caloric intake is insufficient);

- CHILD WASTING: the share of children under the age of five who are wasted (that is, who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition);

- CHILD STUNTING: the share of children under the age of five who are stunted (that is, who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition); and

- CHILD MORTALITY: the mortality rate of children under the age of five (in part, a reflection of the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments).

Understanding hunger:

- Hunger is usually understood to refer to the distress associated with a lack of sufficient calories.

- The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines food deprivation, or undernourishment, as the consumption of too few calories to provide the minimum amount of dietary energy that each individual requires to live a healthy and productive life, given that person’s sex, age, stature, and physical activity level.

Analysing data:

- The data on deficiency in calorie intake, accorded 33% weight, is sourced from the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Suite of Food Security Indicators (2021).

- If GHI had used the latest data on calorie intake, usually provided by the National Sample Survey Office, things might have looked even worse.

- The leaked report of 2019 indicated that consumption expenditure in India declined between 2011-12 and 2017-18 by 4% which is worse for rural India.

- The data on child wasting and stunting (2016-2020), each accounting for 16.6% of weight, are from the World Health Organization, UNICEF and World Bank, complemented with the latest data from the Demographic and Health Surveys.

- Under-five mortality data are for 2019 from the UN Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation.

Questionable component:

- The GHI is largely children-oriented with a higher emphasis on undernutrition than on hunger and its hidden forms, including micronutrient deficiencies.

- The lower calorie intake does not necessarily mean deficiency as it may also stem from reduced physical activity, better social infrastructure (road, transport and healthcare) and access to energy-saving appliances at home, among others.

- Recent analysis establishes that ‘physical disease environment’ at the State level also significantly influences the calorie intake.

- For a vast and diverse country like India, using a uniform calorie norm to arrive at deficiency prevalence means failing to recognise the huge regional imbalances in factors that may lead to differentiated calorie requirements at the State level.

- From this vantage point, a large proportion of the population in Kerala and Tamil Nadu may get counted as calorie deficient despite them being better in nutritional outcome indicators.

States need further calories:

- The States such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh have a higher average level of calorie intake, but their needs may even be higher than the earmarked level of required calories for India as a whole.

- These States further need calories intake due to having high prevalence of communicable diseases and low level of mechanisation in the economy.

- Thus, it is likely that the existing methodology might underestimate the prevalence of calorie deficiency in these States.

- All this raises questions on the appropriateness of the calorie component of the index.

The wasting and stunting:

- The GHI highlights India’s dismal record on child undernutrition. India’s wasting prevalence (17.3%) is one among the highest in the world.

- Its performance in stunting, when compared to wasting, is not that dismal, though.

- Child stunting in India declined from 54.2% in 1998–2002 to 34.7% in 2016-2020, whereas child wasting remains around 17% throughout the two decades of the 21st century.

Needs effective monitoring:

- Stunting is a chronic, long-term measure of undernutrition, while wasting is an acute, short-term measure.

- Child wasting can manifest as a result of an immediate lack of nutritional intake and sudden exposure to an infectious atmosphere.

- If India can tackle wasting by effectively monitoring regions that are more vulnerable to socioeconomic and environmental crises, it can possibly improve wasting and stunting simultaneously.

- Unfortunately, India lost this opportunity as Integrated Child Development Scheme services were either non-functional or severely disrupted — partly because the staff and services were utilised to attend to the COVID-19 emergency.

Improved child mortality:

- India relatively performs better in the other components of GHI such as child mortality.

- Studies suggest that child undernutrition and mortality are usually closely related, as child undernutrition plays an important facilitating role in child mortality.

- India’s child mortality rate has been lower compared to Sub-Saharan African countries despite it having higher levels of stunting.

- This implies that though India was not able to ensure better nutritional security for all children under five years, it was able to save many lives due to the availability of and access to better health facilities.

Conclusion:

- The low ranking for India needs to be taken as a challenge in a positive sense and improve it by looking at our policy focus and interventions by effectively addressing the concerns raised by the GHI, especially against pandemic-induced nutrition insecurity.