(Mains GS2 : Issues relating to development and management of Social Sector/Services relating to Health, Education, Human Resources.)

Context:

- Despite being ‘Pharmacist of the World’, the Out-Of-Pocket-Expenditure (OOPE) in India for health is one of the highest in the world.

Burden of expenditure:

- Post-Independence, the Indian pharmaceutical market was dominated by patented western medicines, unaffordable to the larger public.

- The Patents Act of 1970 abolished product and process patenting, which effectively meant that India now had the chance to reverse engineer and domestically manufacture medicines.

- Manufacturing firms grew in thousands and by the end of the 1980s, India was exporting affordable and effective medicines and vaccines to the whole world.

Issue of branded generic:

- However, medicines were getting cheap and more widely available, but unaffordability remained a concern as medicines continued to constitute a large part of OOPE.

- It is because of the higher cost of branded generics which are the most heavily consumed (figures quote between 70-80 percent or even 90 percent of the share).

- Unbranded ones, on the other hand, are not tagged by any brand but both nearly provide the same efficacy, but manufacturers use the tag of a brand to instill assurance of greater quality.

unscrupulous practices:

- It is this brand differentiation that makes branded generics cost significantly higher than unbranded ones.

- Pharmaceutical companies employ a wide range of brand differentiation and visibility tactics in the face of cutthroat competition in India.

- They reach doctors via marketing representatives, promising incentives and gifts such as free vacations and conferences in exchange for prescriptions of their brands.

- Coupled with a patient’s attitude of ‘no-compromise’ on healthcare, a doctors’ recommendation of a particular brand effectively negates the possibility of a patient choosing an unbranded medicine.

Lacks in public healthcare:

- Hospitals in the public sector pose a larger gamut of issues for patients as most patients do not prefer them because of lack of hygiene and disrespectful treatment.

- There are shocking instances of doctor absenteeism in public healthcare, probably because of low financial incentives.

- There is a lack of reliable infrastructure and technologies, with only one bed available for every 2000 individuals.

- Thus, out of what Indians spend for healthcare, medicines constitute the highest share (72 percent in rural, 70 percent in urban), followed by hospitalization (getting admitted, tests, consultation) and non-hospitalisation (transit, food, etc.) expenses.

Need radical reform:

- Investments in public hospitals and primary healthcare centres are not enough, given the sheer size and healthcare needs of the population.

- The State has historically regulated the prices of medicines via the Drug Price Control Orders, which cap the price rise of molecules, particularly for widespread and life-threatening diseases.

- However, medicines continue to constitute a large part of the OOPE because they are not financed by the State. To finance medicines and avert margins of supply chain stakeholders, some states like Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan procure cheap unbranded generics from manufacturers and via centralised agencies sell it directly to the patients.

- Extending this to private providers also would radically change OOPE for medicines.

Conclusion:

The major caveats in healthcare delivery and affordability show us that health is always a matter of political priority, and universal healthcare is possible only if it is a budgetary, political and economic priority.

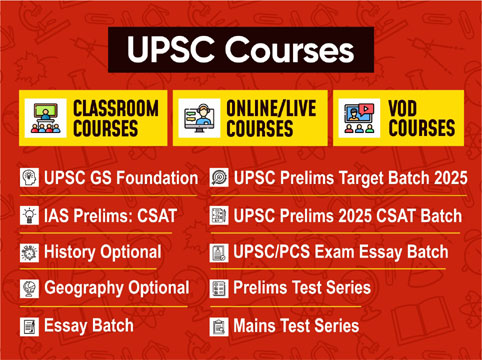

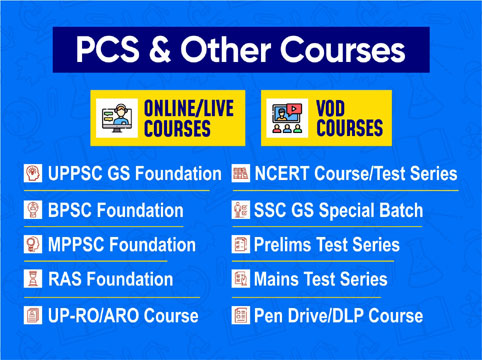

Contact Us

Contact Us  New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757

New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757  Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757

Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757