|

Syllabus : Prelims GS Paper I : Current Events of National and International Importance. Mains GS Paper III : Effects of Liberalization on the Economy, Changes in Industrial Policy and their Effects on Industrial Growth. |

India should zealously boost export performance and deploy all means to achieve that because India does not have the luxury of abandoning export orientation.

India has focused on domestic-demand led growth not just as a short-run response to Covid – 19, but as a medium-term growth strategy. All the evidence across the world and in India has shown that rapid and sustained economic growth requires export dynamism. India’s GDP growth of over 6 per cent after 1991 was associated with real export growth of about 11 per cent. Pre-1991, a 3.5 per cent growth rate was associated with export growth of about 4.5 per cent. There is no known model of domestic demand/consumption-led growth, anywhere or at any time, that has delivered quick, sustained, and high (say 6 plus) rates of economic growth for developing countries.

But even leaving aside the desirability of exports over domestic demand led growth, how feasible is the latter today? Policies that could achieve this are: More public spending, tax cuts to boost private consumption and private investment, and/or financial sector reform to boost private investment.Against the current backdrop of bleeding public, financial, and household and private sector balance sheets, these policies look difficult. Only growth can rehabilitate balance sheets; stressing balance sheets further cannot realistically revive growth. Consumption growth will be limited by the fact that household debt has grown rapidly in the last few years.

Consumption now can grow only if incomes grow.Government spending could be a short run option, but COVID has limited that possibility. Post-COVID, India’s debt is expected to rise from about 70 per cent of GDP to about 85-90 per cent and deficits are likely to be in the double-digit range. The fiscal space for spending will be severely limited both because of high levels of deficits and indebtedness and because debt dynamics will be adverse unless growth picks up substantially.India should be cautious about succumbing to intellectual mimicry of advanced countries on fiscal policy. India’s interest rates are not at zero and are unlikely to be so because of persistent inflation. India’s borrowing is still considered risky, reflected in ratings that are hovering perilously close to being classified as sub-par. The favourable interest rate-growth differential that supports expansionary policy in the advanced countries is absent in India. India may well have scope for expansionary fiscal policy in the short run but not as a medium run growth strategy.India’s financial system was badly impaired even heading into the COVID crisis and will come out more seriously damaged. Given the limited progress in fixing the financial system, prospects for investment remain weak. In short, in India’s current circumstances, India does not have the luxury of abandoning export orientation because the alternatives are so limited.

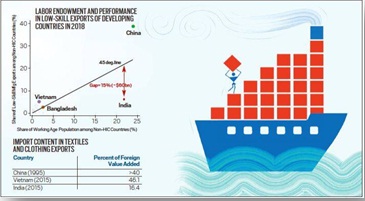

If exports are critical, can the recent recourse to protectionist policies deliver? India’s market is too small to sustain any kind of serious import substitution strategy or even as a way of offering investors the domestic market as bait and incentivising them to export. India’s big, unexploited opportunities are in unskilled labour exports. We expect that countries should line up roughly along the 45 degree line so that outcomes (exports) match endowments (unskilled labour force). China and India are stark outliers but in the opposite direction. China is vastly over-exporting. India is vastly under-exporting relative to its labour force. We estimate that India is producing and exporting about $60-$140 billion (2-5 per cent of GDP) less of low-skilled activity annually than it should be. There are, of course, two ways to look at this finding. On the one hand, it is an indictment of past performance. On the other, it is also an indicator of potential future opportunity if the underlying problems are addressed.In recent years, because China’s wages are rising as it has become richer, it has vacated about $140 billion in exports in unskilled-labour intensive sectors, including apparel, clothing, leather and footwear. Post-COVID, the move of investors away from China will probably accelerate as they seek to hedge against supply chain disruptions because of trade actions against China. India did not take advantage of the first China opportunity. Now, a second opportunity stemming from geo-politics has been created and that is India’s big prize waiting to be seized.Importantly, exploiting this opportunity in unskilled exports requires more not less openness. To be internationally competitive, many parts and components have to be imported from so many different sources that openness is an existential necessity not a luxury. One indicator is the foreign or import contribution to exports. Comparing China and Vietnam at roughly the time of their export boom in textiles and clothing suggests that exports were highly dependent on imports (between 40 and 45 per cent). In contrast, India’s import share is about 16 per cent. Achieving Chinese and Vietnamese levels of success will therefore require greater imports and openness.In the case of clothing, a key policy change in India will be to eliminate tariffs on all inputs. Especially the long-standing tariff on man-made yarn because man-made fibre-based exports (not cotton-based apparel) are the most dynamic segment of world exports. It will also require signing free trade agreements with Europe that still impose high duties on India’s clothing exports of close to 10 per cent which disadvantages India relative to Bangladeshi and Vietnamese exports which enjoy preferential access to world markets. But Europe will only be willing to sign such an agreement if India is willing to open its other markets (for example, automotives). Export success will also require genuine easing of costs of trading and doing business in India. As India contemplates atmanirbharta, two deeper advantages of export orientation are always worth remembering. First, foreign demand will always be bigger than domestic demand for any country. Second, there is also a fundamental asymmetry: If domestic producers are competitive internationally, they will be competitive domestically and domestic consumers and firms will also benefit. The reverse is not true: Being competitive only domestically is no guarantee of efficiency and low cost.In sum, resisting the misleading allure of the domestic market, India should zealously boost export performance and deploy all means to achieve that. Pursuing rapid export growth in manufacturing and services should be an obsession with self-evident justification. Abandoning export orientation will amount to killing the goose that lays the golden eggs and indeed killing the only goose laying the eggs. Alas, to embrace atmanirbharta is to choose to condemn the Indian economy to mediocrity.

Action plans should be prepared to ensure success of Atmanirbhar Bharat project:

COVID-19 took very little time to spread across the world economy. International trade has been constricted and global supply chains have, by and large, been disrupted. Each nation has been left to fend for itself. India’s dependence on other countries has been exposed in several areas. The country should now refocus on manufacturing, and be self reliant.Prime Minister Narendra Modi gave a call to fellow Indians to be “Vocal for Local” in May. This essentially means, as PM Modi explained, not only to buy and use local products, but to also take pride in promoting them. The Centre announced a well-considered programme, the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (ANBA), as part of the post-pandemic economic revival package. Rs 20 lakh crore (10 per cent of India’s GDP) was earmarked for the purpose.Nevertheless, experts and industrialists do assert that the ANBA is an excellent initiative and gives India the opportunity to embark on the self-reliance drive.

Suggestions to take the mission forward systematically, and in a spirit of accountability:

1. An umbrella action plan should be drawn by the Niti Aayog listing all possible categories of targets under the ANBA and the Vocal for Local Mission. A monitoring agency will review and suggest course correction to ensure that no delay is allowed to build.

2. Second, each state/UT will develop an action plan in consonance with the umbrella plan — with a similar agenda and a robust mechanism.

3. A separate organisation created by each state will be responsible for the implementation of the action plan, as well as running all related operations on a day-to-day basis. It will also conduct regular studies to identify local and global market trends and invite competitive solutions to meet market demands.

4. Each district (or a group of districts) will work out a more detailed action plan, and charter of responsibilities for ground level officers and departments. The district action plan should incorporate the setting up of certain bodies/groups.

First, an autonomous authority to be headed by an additional DM or a technocrat to manage and pilot the implementation of the listed measures on ground, and be solely accountable for timely delivery. Its other important targets will include scaling up and setting up of a certain number of companies/ industries/manufacturing units over a fixed time period. The authority will also set up a 24X7 facilitation centre to help the existing and the newcomer companies and resolve their doubts and disputes. This agency will also be responsible for creating public awareness amongst all stakeholders.Another group in the district authority will be tasked to lay out detailed norms and guidelines on safe working conditions in each sector. It will be responsible for matters related to workers’ families welfare, particularly in respect of health, education, and decent civic conditions.The state/ UT and district authorities should be headed by a few hand-picked officers. This can also be done by inviting volunteers from amongst the eligible officers. The state government will facilitate regular interactions amongst district authorities and help develop sector-speci strategies.

The ANBA is a mission to empower the people of India. It is like a “yagya”, to be performed in that spirit of purity, not only by the executive machinery but also by the people in placing their faith in the spirit and mandate of this mission. It will in all likelihood become a benchmark of how governments and their various organisations can work in a mission mode.

India’s export opportunities could be significant even in a post-COVID world:

India’s intellectual and policy community has embraced atmanirbharta. This inward turn — actually return — amounts to abandoning two core principles of the post-1991 consensus: Export-orientation on the macro-economic side, and slow but steady liberalisation on the trade side. Is the inward turn strong? Is the underlying diagnosis-cum-prognosis correct? Will it work? Based on new research, our simple answers are, respectively: Yes; no; and not really. The inward turn is most evident in trade policies aimed at promoting domestic manufacturing. Leaving aside the spate of China-related restrictions, tariffs have been increased substantially, trade agreements have been put on hold, and a spate of production subsidies are being offered.Between 1991 and 2014, average tariffs declined from 125 per cent to 13 per cent. However, since 2014, there have been tariff increases in 3,200 out of 5,300 product categories, affecting about $300 billion or 70 per cent of total imports. The average tariff increased from 13 per cent in 2014 to nearly 18 per cent. The largest increases occurred in 2018 when tariffs for nearly 2,500 product categories were increased, amounting to nearly 4 percentage points. Tariff increases have been greatest in low-skill manufactured imports and cell-phone assembly, amounting to 10-15 percentage points.The inward turn is based on three misconceptions of diagnosis and prognosis. First, the perception is that India’s growth success since 1991 has not really been based on exports and certainly not on manufacturing exports. This is wrong. India has been a model of spectacular export success and an exemplar of export-led growth.Between 1995 and 2018, India’s overall export growth (in dollars) averaged 13.4 per cent annually, the third best performance in the world amongst the top 50 exporters. Most strikingly, India’s manufacturing exports (in dollars) — for long considered India’s Achilles Heel — grew on average by a whopping 12.1 per cent, the third-best performance in the world, and nearly twice the world average . Only China and Vietnam surpassed India.These exports made a substantial contribution to the overall GDP growth. In each of the three decades since the 1990s, exports contributed about one-third of overall growth. As a result, India’s export-GDP ratio is currently 20 per cent, more than twice as high as in the early 1990s, despite the post-global financial crisis (GFC) slowdown. Thus, an export slowdown today is likely to have a more consequential impact on the overall economy. Every 5 per cent of the export growth foregone will shave off 1 per cent in overall GDP growth.The second is a pessimistic prognosis about India’s future exports. This overlooks key facts. Export pessimism is based on expectations of de-globalization abroad and weak performance at home. But India can gain market share even in a de-globalizing world. Consider the numbers. India’s manufacturing exports account for 1.7 per cent of the world’s which is less than Vietnam’s. Even if India’s exports grow three-to four times as fast as the world exports, it would gain only a few percentage points of the global market share after 10 years. China’s secular ceding of low-skill export space provides further opportunity. This is one of the virtues of past under-performance: The future can be more accommodating to India and less intimidating for the world.This possibility is not just hypothetical. It is exactly what India did after the global financial crisis. In the 2010s, world exports were stagnant and yet India’s exports grew by about 3 per cent. This was true in both manufacturing and services.

The lamentation about deterioration in export performance in the 2010s (especially post-2014) is ironic given that it was partly self-inflicted. It was caused by a domestic anti-export policy, including a sharp exchange rate appreciation of 20 per cent, reputational damage that undermined pharmaceutical exports, and a social policy — on livestock — that affected agricultural exports. Not only did India’s exports hold up as global trade collapsed, they could have held up even more had domestic policies not been so inimical.The real prize that India should aim for is the large unexploited opportunity of unskilled labour exports — around $140 billion which we discuss in our second column. The other under-recognised opportunity is in services. The post-global financial crisis era witnessed de- globalization of world trade in goods but globalization continued apace in services. World exports of goods peaked just prior to the GFC at about 25 per cent, declining to about 21 per cent in 2019. However, world exports of services which reached 6.5 per cent in the GFC, took a hit, but have since steadily risen to about 7 per cent.COVID could even create an upside potential to globalization. Consumption and production activities that require close physical contact will fare worse. The flip side is that activities that can be done at a distance — and tradable services are exactly that — could benefit enormously. If so, they could play to India’s comparative advantage in service exports. Atmanirbharta’s third driver is the strong belief that India’s market is big enough to sustain growth going forward and make up for the loss of opportunities overseas. Size seduces. At $2.9 trillion, and as the fifth largest in the world, India’s GDP seems alluringly big. But if the domestic market is to sustain growth, we need to look at the size of the market (say the “middle class”) with some amount of purchasing power over manufacturing goods and services.Based on some assumptions, our rough estimate is that this middle class market size is between 15 and 40 per cent of GDP. This is smaller than commonly believed and substantially smaller than any potential world market that Indian firms and producers can and should compete for. The reason is twofold. There are a lot of poor people with limited purchasing power and a few people with a lot of purchasing power who, however, save a lot. Both of these reduce the market for consumption. The delusion of size is making policy-makers set their sights on the domestic market when it should be on the world market.Normally, it is failure that is an intellectual orphan. In contrast, India’s inward turn seems to be a case of making an orphan of spectacular success. India’s growth model has been an export-led one and should not be abandoned. Moreover, India’s export opportunities in general and in specific sectors could be significant even in a post-COVID world.

The global economic implications of COVID are unmodellable. India missed the manufacturing export train that China boarded but another may be coming. Even if it isn’t, India’s economy is weaker than predicted by Harvard economist Ricardo Hausmann’s economic complexity model. Our high economic complexity has not translated into economic prosperity because of regulatory cholesterol whose removal has begun. Policy reform is not the solving of a sum but the painting of a picture — 90 days after the lockdown ends, we need ANBA 2.0 to finish the job.

Measuring the Depth:

PreQ: With reference to India’s export-GDPconsider the following Statement:

1. India’s export-GDP ratio is currently 20 per cent, more than twice as high as in the early 1990s, despite the post-global financial crisis (GFC) slowdown.

2. Every 5 per cent of the export growth foregone will shave off 1 per cent in overall GDP growth.

Which of the above statements is/ are correct ?

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 only

(c) Both 1 and 2

(d) Neither 1 nor 2

Q.Mains: What are India’s export prospects in post Covid – 19 scenario and how Atmanirbhar Bharat will help to boost export orientation as well as GDP ? Discuss.

Our support team will be happy to assist you!