(MainsGS3:Disaster and disaster management.)

Context:

- Recently, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) warned that the maximum temperatures over northwest, west, and central India would be 3-5° C higher than the long-term average.

Temperature deviation:

- Irrespective of whether these are freak occurrences, heat waves are expected to become more intense, longer, and more frequent over the Indian subcontinent.

- According to the IMD, a region has a heat wave if its ambient temperature deviates by at least 4.5-6.4° C from the long-term average.

- There is also a heat wave if the maximum temperature crosses 45° C (or 37° C at a hill-station).

- Spring (March-April) in 2022 in India was already a sign of things to come: the heat wave ‘season’ started early, was more intense than the long-term average, and had more waves.

Occurrence of heatwaves:

- The 2022 heatwave season was also unusual because the heat waves extended much further south into peninsular India thanks to a north-south pressure pattern set up by the La Niña, a world-affecting weather phenomenon in which a band of cool water spreads east-west across the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

- The last three years have been La Niña years, which has served as a precursor to 2023 likely being an El Niño year.

- The El Niño is a complementary phenomenon in which warmer water spreads west-east across the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

Origin of heat waves:

- Heat waves are formed for one of two reasons: because warmer air is flowing in from elsewhere or because something is producing it locally.

- Air is warmed locally when the air is warmed by higher land surface temperature or because the air sinking down from above is compressed along the way, producing hot air near the surface.

- The other factors that affect the formation of heat waves are the age of the air mass and how far it has travelled.

- The north-northwestern heatwaves are typically formed with air masses that come from 800-1,600 km away and are around two days old.

- Heat waves over peninsular India on the other hand arrive from the oceans, which are closer (around 200-400 km) and are barely a day old thus, they are on average less intense.

Direction of airflow:

- A study published on February 20, 2023, in Nature Geoscience offers some clues as to how different processes contribute to the formation of a heat wave.

- In spring, India typically has air flowing in from the west-northwest and in the context of climate change, the Middle East is warming faster than other regions in latitudes similarly close to the equator, and serves as a source of the warm air that blows into India.

- Likewise, air flowing in from the northwest rolls in over the mountains of Afghanistan and Pakistan, so some of the compression also happens on the leeward side of these mountains, entering India with a bristling warmth.

- The air flowing over the oceans is expected to bring cooler air, since land warms faster than the oceans (because the heat capacity of land is much lower). Alas, the Arabian Sea is warming faster than most other ocean regions.

Westerly winds:

- The strong upper atmospheric westerly winds that come in from the Atlantic Ocean over to India during spring control the near-surface winds.

- Any time winds flow from the west to the east, we need to remember that the winds are blowing faster than the planet itself, which is also rotating from west to east.

- The energy to run past the earth near the surface, against the surface friction, can only come from above and this descending air compresses and warms up to generate some heat waves.

Declining lapse rate:

- Finally, the so-called lapse rate – the rate at which temperatures cool from the surface to the upper atmosphere – is declining under global warming.

- In other words, global warming tends to warm the upper atmosphere faster than the air near the surface.

- This in turn means that the sinking air is warmer due to global warming, and thus produces heat waves as it sinks and compresses.

Conclusion:

- Sizeable investments in human and computational resources have already increased India’s forecast skills in the last decade.

- But we should also not become complacent, and further improve forecast warnings, issue them as soon as possible, and couple them with city-wide graded heat action plans to protect the vulnerable.

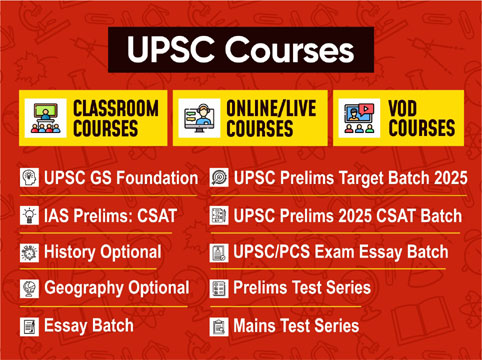

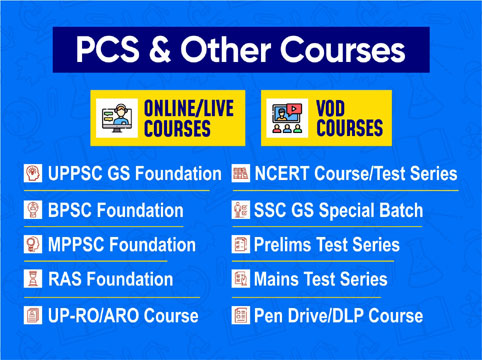

Contact Us

Contact Us  New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757

New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757  Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757

Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757