(Mains GS 1: Role of women and women’s organization, population and associated issues, poverty and developmental issues, urbanization, their problems and their remedies.)

Context:

- On March 31, the World Economic Forum released its annual Gender Gap Report 2021.

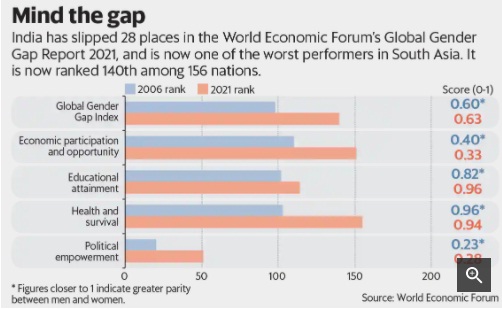

- India had slipped 28 spots to rank 140 out of the 156 countries covered.

- For the 12th time, Iceland is once again the most gender-equal country in the world.

Key findings of the report:

- The report is a measure of gender gap on four parameters: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment.

- The data show that it will take 135.6 years to bridge the gender gap worldwide and the pandemic has impacted women more severely than men.

- The gap is the widest on the political empowerment dimension with economic participation and opportunity being next in line.

- Within the 156 countries covered, women hold only 26 per cent of parliamentary seats and 22 per cent of ministerial positions.

- India in some ways reflects this widening gap, where the number of ministers declined from 23.1 per cent in 2019 to 9.1 per cent in 2021.

- The number of women in Parliament stands low at 14.4 per cent.

- However, the gap on educational attainment and health and survival has been practically bridged.

Gender approach needs mainstreaming:

- In a time when 104 countries still have laws preventing women from certain types of jobs, and over 600 million women live in countries where domestic violence is not punishable, a gendered approach has to be mainstreamed into broader policy objectives.

- This means going beyond conventional considerations of development assistance and domestic policies to include core areas of foreign policy, economics, finance, trade and security.

- This also means that along with increasing representation, women and marginalised sections of society need to have a voice to provide alternative perspectives to policy making.

A femininist foreign policy approach:

- A feminist foreign policy as a political framework can ensured voice of women and marginalised sections of society will be heard and increasing women representation in political affairs , first introduced and advocated by Sweden in 2014.

- Feminist approaches to international affairs can be traced back to the 1980s, though largely rooted in traditional thinking and activism.

- In many ways feminist foreign policy translated to a bottom-up development approach, especially with a donor-based mindset, albeit often with caveats.

- While this slowly changed in the 1990s, core areas of security and diplomacy were still the domain of men, and remain so.

- The realisation that it is not only necessary to include women in peacebuilding and peacekeeping but the wider gamut of diplomacy and foreign and security policy is growing.

- Data also indicate that the inclusion of diverse voices makes for a better basket of options in decision making and is no longer simply a virtuous standard to follow.

Needs greater diversity in thinking:

- Since Sweden embarked on this path, several other countries likeCanada, France, Germany and, more recently, Mexico have forged their own, adopting either a feminist foreign policy or a gendered approach to aspects of policy making.

- However, the current conversation around a feminist/gendered foreign policy is still largely in small circles in North America and Europe.

- Greater diversity in thinking will allow for a global policy to be tailored and thus operationalised in a wider geography, accounting for vastly divergent social norms and practices, and lived histories.

India has a key role to play:

- As a non-permanent member of the UNSC and recently elected to the UN Commission on the Status of Women for a four year term in September 2020, India has a key role to play.

- Gender considerations in India’s foreign policy are not new. Though located largely under the development assistance paradigm and peacekeeping, these have been incredibly successful.

- From 2007 when India deployed the first ever female unit to the UN Mission in Libya to supporting gender empowerment programmes through SAARC, IBSA, IORA and other multilateral fora, India's programmes have been targeted at making women the engines for inclusive and sustainable growth.

- Many of India's overseas programmes in partner countries have a gender component, as seen in Afghanistan, Lesotho and Cambodia.

- In India also, 2015 saw a gender budget exercise within the MEA towards development assistance.

Need more formal design approach:

- India needs a more formal designed approach that goes beyond a purely development model to wider access, representation and decision making.

- The WEF report and other similar indices is a call to do better on the domestic front; no matter how “feminist” our foreign and security policy might be, without balance at home it will not last.

- India’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Ambassador T N Trimurti said India's election to the CSW (Commission on the Status of Women) was a “ringing endorsement of our commitment to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment in all our endeavours”.

Conclusion:

- India must now go further to sensitise and shape global discussions around gender mainstreaming.

- Country’s gender-based foreign assistance needs to be broadened and deepened and equally matched with lower barriers to participation in politics, diplomacy, the bureaucracy, military and other spaces of decision making.

- In doing this, India can easily claim a new unique feminist foreign policy adding to and smartly shaping the global conversation.