(MainsGS2:Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.)

Context:

- The Director General of Health Services (DGHS) issued an order reiterating directions that doctors in Central government hospitals prescribe only generic medicines instead of branded drugs.

Writing the generic medicines:

- The driving force behind these office orders is the standard trope that doctors are in cahoots with the pharmaceutical industry wherein the doctor receives a kickback for each prescription of a particular company’s drug.

- Thus, by forcing them to write only the generic names of medicines, the hope is that the pharmacist will provide the patient with the cheapest available generic drug and thus save them the cost of the more expensive branded drugs.

Lack of trust:

- But the Directorate should conduct a survey among government doctors asking them to explain their reluctance to write prescriptions with just the generic names.

- As it is no secret that many Indian doctors in both the public and private sector simply do not trust the quality of all generic medicines in the Indian market.

- They have a valid reason for this because India has lagged behind countries like the U.S. in creating the appropriate legal and scientific standards that provide guarantees to doctors on the interchangeability of generic medicines with each other and the innovator drug.

Bio-equivalent:

- The U.S. created this environment of trust by mandating as far back as in 1977 that most, but not all, generic drugs be tested on human volunteers in order to measure the rate at which the drug is bioavailable; i.e. the rate at which the drug dissolves in the bloodstream.

- Such testing is required because generic manufacturers may use different excipients like binders, coating and punching machines which directly affect the ability of the drug to dissolve in the blood.

- If the dissolution profile of the generic drug is same or similar to that of the innovator drug over a time period, it is declared to be “bio-equivalent” and hence therapeutically interchangeable with the innovator drug.

India’s perspective:

- India mandated such bio-equivalence testing only in 2017 and even then, the regulations were vague.

- But the far more worrying aspect from a public health perspective is the fact that a recommendation by the Drugs Technical Advisory Board (DTAB) to ensure that existing generic drugs, approved prior to 2017, also be tested for bio-equivalence, was ignored by the government.

- This means that a vast majority of drugs in the Indian market have never been tested for bio-equivalence.

- Hence, the government cannot provide doctors with a legal guarantee that all generic medicines in the Indian market are, in fact, interchangeable with the innovator drug.

- Thus, many doctors have developed faith in particular brands, not because they receive bribes but because patient feedback has taught them that other brands do not work as effectively.

Conclusion:

- Given these issues related to the quality of generic drugs, a starting point would be to ask for regulations which require pharma companies to identify on their packaging whether a drug has been tested for bio-equivalence and stability as required by the law.

- Thus, building the confidence of doctors in generic medicine serves public interest better than threatening them with punitive action for failing to comply with directives on mandatory prescription of drugs by their generic names.

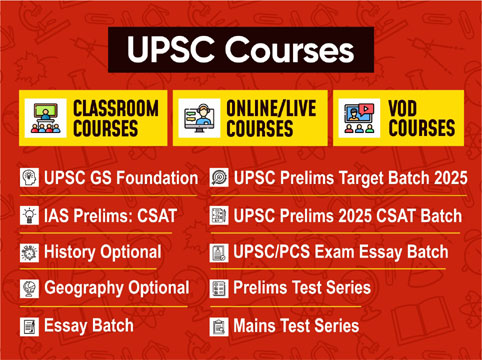

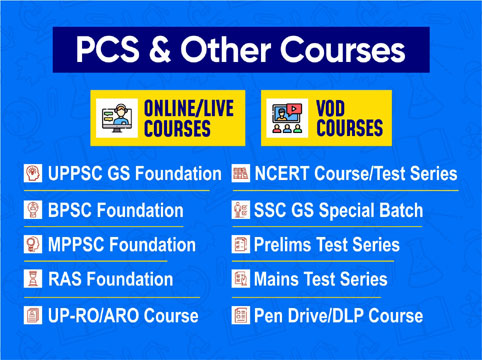

Contact Us

Contact Us  New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757

New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757  Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757

Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757