(Mains GS 2 : Issues relating to poverty and hunger.)

Context:

- The Consumption Expenditure Survey (CES) which is conducted by the National Sample Survey Office (NSO) every five years has not released the data since 2011-12.

- The CES of 2017-18 was not made public by the Government of India and a new CES is likely to be conducted in 2021-22.

- Meanwhile, unemployment had reached a 45-year high in 2017-18, as revealed by NSO’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS).

Sufficient to estimate change:

- India’s labour force surveys, including the five-yearly Employment-Unemployment Rounds from 1973-4 to 2011-12, have also collected consumption expenditure of households.

- While the PLFS’s questions on consumption expenditure are not as detailed as those of the CES, they are sufficient for us to estimate changes in consumption on a consistent basis across time.

- It enables us to estimate the incidence of poverty (i.e., the share in the total population of those below the poverty line), as well as the total number of persons below poverty.

Poverty incidences:

- There is a clear trajectory of the incidence of poverty falling from 1973 to 2012.

- In fact, since India began collecting data on poverty, the incidence of poverty has always fallen, consistently.

- It was 54.9% in 1973-4; 44.5% in 1983-84; 36% in 1993-94 and 27.5% in 2004-05.

- This was in accordance with the Lakdawala poverty line (which was lower than the Tendulkar poverty line).

Methodology for poverty line:

- In 2011, it was decided in the Planning Commission, that the national poverty line will be raised in accordance with the recommendations of an expert group chaired by the late Suresh Tendulkar.

- That is the poverty line which is used in estimating poverty in India.

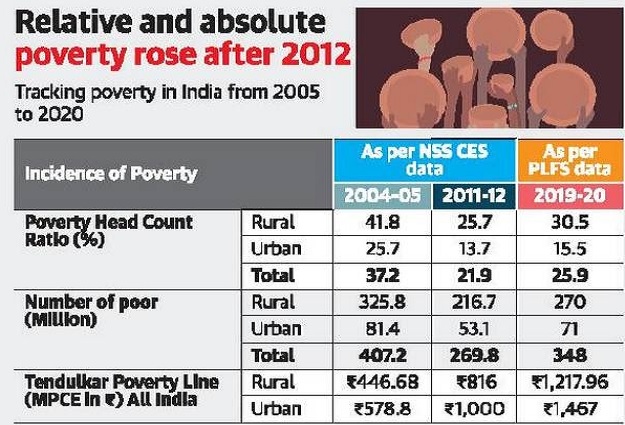

- The Suresh Tendulkar Committee report at a ‘line’ of ₹816 per capita per month for rural India and ₹1,000 per capita per month for urban India, calculated the poor at 25.7% of the population.

- While the C. Rangarajan Committee, which in 2014 estimated that the number of poor were 29.6%, based on a person's spending below ₹47 a day in cities and ₹32 in villages.

- This poverty line was comparable at the time to the international poverty line (estimated by the World Bank), of $1.09 (now raised to $1.90 to account for inflation) person per day.

An urban and rural rise:

- It is estimated that for the first time in India’s history of estimating poverty, there is a rise in the incidence of poverty since 2011-12.

- The rural consumption between 2012 and 2018 had fallen by 8%, while urban consumption had risen by barely 2%.

- Since the majority of India’s population (certainly over 65%) is rural, poverty in India is also predominantly rural.

- Remarkably, by 2019-20, poverty had increased significantly in both the rural and urban areas, but much more so in rural areas (from 25% to 30%).

The absolute number of poor has risen:

- It is for the first time in India’s history since the CES began that we have seen an increase in the absolute numbers of the poor, between 2012-13 and 2019-20.

- Estimates reflected from 217 million in 2012 to 270 million in 2019-20 in rural areas; and from 53 million to 71 million in the urban areas; or a total increase of the absolute poor of about 70 million.

- In March, the Pew Research Center with the World Bank data estimated that ‘the number of poor in India, on the basis of an income of $2 per day or less in purchasing power parity, has more than doubled to 134 million from 60 million in just a year due to the pandemic-induced recession’.

The contributory factors:

- The reasons for increased poverty are policy flaws and Covid pandemic.

- The demonetisation followed by an introduction of Goods and Services Tax delivered a severe jolt to the unorganised sector and Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

- The four engines of growth were not performing up to their potential.

- Private investment fell from 31% inherited by the new government, to 28% of GDP by 2019-20.

- Public expenditure was constrained by a silent fiscal crisis.

- Exports, which had never fallen in absolute dollar terms for a quarter century since 1991, actually fell below the 2013-14 level ($315 billion) for five years.

- Consumption stagnated and household savings rates fell.

- Joblessness increased to a 45-year high by 2017-18 (by the usual status), and youth (15-29 years of age) saw unemployment triple from 6% to 18%.

- Real wages did not increase for casual or regular workers over the same period, hardly surprising when job seekers were increasing but jobs were not at anywhere close to that rate.

- Hence, consumer expenditure fell, and poverty increased.

- Further the COVID-19 pandemic gives an absolute jolt to the economy as global supply disrupts and lockdown is imposed to save lives.

Conclusion:

- The almost sub-human level of existence of the majority of fellow Indians cannot be continued.

- Thus, the massive slide into poverty in India that is clear in domestic and international surveys and anecdotal evidence must meet with an urgent institutional response.