(Mains GS 3 : Issues Relating to Development and Management of Social Sector/Services relating to Health, Education, Human Resources.)

Context:

- Engel’s Law stated that the poorer a family, “the greater the proportion of the total outgo which must be used for food and the proportion of the outgo used for food, if other things being equal, is the best measure of the material standard of living of a population.”

- An analysis based on the CMIE Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (January 2019-August 2021) to examine spells of impoverishment during the pandemic in India reveals that it is not just food expenditures that differ but also diets in different sections of the society.

During the pandemic:

- The caste-based hierarchy is deep-seated in India, with the Brahmins and other upper castes at the top, and the Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) at the bottom.

- Traditionally, Brahmins are vegetarian, while SCs and STs are not and Hindus in India are better-off than Muslims on average.

- While many Hindus are vegetarian, many also eat meat with the exception of beef and Muslims are non-vegetarian and are allowed to eat all kinds of meat except pork.

Rise in food shares:

- The shock of the pandemic caused breakdowns in food supply chains and a fall in food demand which is a consequence of loss of income.

- Amidst the misery, food prices spiked as there was speculative hoarding by food sellers and ‘panic buying’ by consumers.

- The lockdowns resulted in a sharp rise in food share across rural and urban India and among all socioeconomic groups comprising various castes and religions, but at different rates.

Shift of expenditure:

- Among SC households in rural areas, the food share ranged from 46% to 54% before March 2020 which surged to about 64% in April 2020 coinciding with the first national lockdown.

- In urban areas, it was the OBCs and Others who saw a sharp rise in food share.

- Among many one reason for the opposing results in rural and urban India could be the shift of expenditure in urban areas by the upper castes to home-cooked food i.e. a change in lifestyle forced by the lockdown and fear of the pandemic.

After restriction lifted:

- Once restrictions were lifted, there was a sharp decline in food share across all groups but food shares were still higher than pre-pandemic levels.

- However, the extent of contraction differed between rural and urban areas and among different castes.

- The food share of SCs recorded the sharpest contraction, followed by Others, STs and OBCs.

- In urban areas, the fall was steepest among the STs, followed by Others, SCs and OBCs.

- However, in rural areas, SCs and STs saw a rise in food shares despite relaxation of restrictions.

Through the religion:

- Different religious groups also experienced a sharp rise in the share of food expenditure in both rural and urban areas.

- The shares of food among rural Hindu households ranged from 44% to 52% prior to March 2020, and among urban Hindu households from 40% to 49%.

- The shares of Muslims in rural areas ranged from 48% to 58%, and in urban areas from 45% to 52% prior to the first lockdown.

- At the onset of the pandemic, urban areas were hit harder than rural areas in terms of rising COVID-19 cases, which may have led to greater shifts in food budget expenditure in urban households.

- However, after April 2020, the shares declined gradually until November 2020 with a steady rise across all religions in both rural and urban areas during the second wave, with a peak of the shares in May 2021.

Alarming rise:

- Food shares may have risen slightly as the informal sector and employment remained sluggish and the food supply chains were far from fully restored.

- But higher food shares are alarming because inferior cereals are substituted for expensive cereals; lower amounts are spent on more nourishing foods such as fruits and vegetables; and other essential non-food items such as education and healthcare are neglected.

- Thus, spells of impoverishment during the pandemic were not infrequent, and lower castes and minorities bore the brunt of it.

Conclusion:

The Budget (2022-23) seeks to promote growth through investments but neglects deficiency of aggregate demand, especially among the deprived shows the lack of sensitivity to the plight of the disadvantaged.

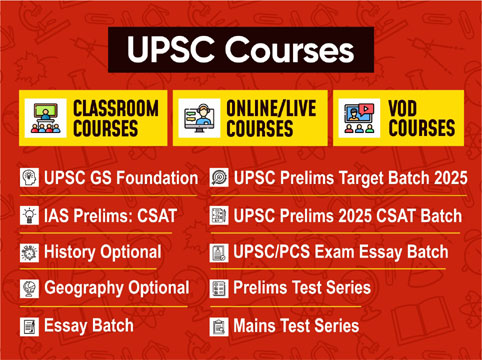

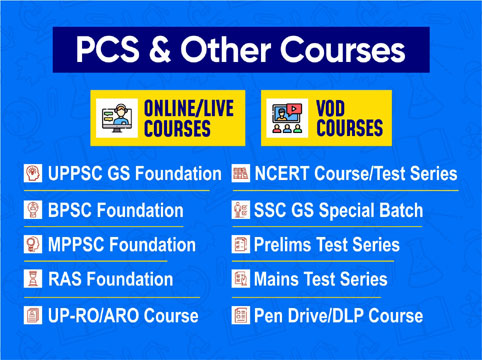

Contact Us

Contact Us  New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757

New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757  Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757

Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757