(Mains GS 3 : Issues related to direct and indirect farm subsidies and minimum support prices; Public Distribution System-objectives, functioning, limitations, revamping; issues of buffer stocks and food security)

Context:

- The demand of farmers to provide a legal guarantee for the minimum support price (MSP) for their produce has triggered a nationwide debate as specialists believe that to procure all the 23 crops on MSP would be “fiscally ruinous” and a logistical nightmare.

Trade distortion:

- India has been a founding member of the WTO and is a signatory to the multilateral Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) which regulates domestic subsidies granted by governments in the agricultural sector.

- The ‘disciplines’ on agricultural subsidies aim to curb trade distorting aid, which, despite being granted domestically, adversely affects the competitiveness of the global market.

- Providing a legal guarantee for MSP will also might violate India’s international law obligations enshrined in the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) of the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Domestic subsidies:

- One of the central objectives of the AoA is to cut trade-distorting domestic support that WTO member countries provide to agriculture.

- In this regard, the domestic subsidies are divided into three categories: ‘green box’, ‘blue box’ and ‘amber box’ measures.

- Subsidies that fall under the ‘green box’ (like income support to farmers de-coupled from production) and ‘blue box’ (like direct payments under production limiting programmes subject to certain conditions) are considered non-trade distorting, hence, countries can provide unlimited subsidies under these two categories.

- However, price support provided in the form of procurement of crops at MSP is classified as a trade-distorting subsidy and falls under the ‘amber box’ measures, which are subject to certain limits.

Aggregate Measurement of Support:

- To measure ‘amber box’ support which is defined under Article 6 of the AoA, WTO member countries are required to compute Aggregate Measurement of Support (AMS).

- AMS is the total of product-specific support (price support to a particular crop) and non-product-specific support (fertilizer subsidy).

- Under Article 6.4(b) of the AoA, developing countries such as India are allowed to provide a de minimis level of product and non-product domestic subsidy.

- This de minimis limit is capped at 10% of the total value of production of the product, in case of a product-specific subsidy; and at 10% of the total value of a country’s agricultural production, in case of non-product subsidy.

- Subsidies breaching the de minimis cap are trade-distorting; thus, they have to be accounted for in the AMS.

External reference price issue:

- The procurement at MSP, after comparing it with the fixed external reference price (ERP) (an average price based on the base years 1986-88) has to be included in AMS.

- Since the fixed ERP has not been revised in the last several decades at the WTO, the difference between the MSP and fixed ERP has widened enormously due to inflation.

- For example: according to the Centre for WTO Studies, India’s ERP for rice, in 1986-88, was $262.51/tonne and the MSP was less than this. However, India’s applied administered price for rice in 2015-16 stood at $323.06/tonne, much more than the 1986-88 ERP.

- When this difference is accounted for in the AMS, the possibility of overshooting the de minimis limit becomes real.

- Thus, procuring all the 23 crops at MSP, as against the current practice of procuring largely rice and wheat, will result in India breaching the de minimis limit making it vulnerable to a legal challenge at the WTO.

Sugarcane case:

- Even if the Government does not procure directly but mandates private parties to acquire at a price determined by the Government, as it happens in the case of sugarcane, the de minimis limit of 10% applies.

- Very recently, a WTO panel in the case, India – Measures Concerning Sugar and Sugarcane, concluded that India breached the de minimis limit in the case of sugarcane by offering guaranteed prices paid by sugar mills to sugarcane farmers.

- However, India has consistently defended its position and emphasised the need to prioritise the food and livelihood security of its population.

Conditional peace clause:

- The peace clause forbids bringing legal challenges against price support-based procurement for food security purposes even if it breaches the limit on domestic support.

- However, the peace clause is subject to several conditions, for example, it can be availed by developing countries for the support provided to traditional staple food crops to pursue public stockholding programmes for food security (procuring food to provide free ration through the Public Distribution System).

- Furthermore, the peace clause is applicable only for programmes that were existing as of the date of the decision and are consistent with other requirements.

- Further countries are also under an obligation to notify the WTO if their subsidies exceed the permissible level for example recently India reported to the WTO that it gave subsidies worth $6.31 billion for rice in 2019-20 while the value of rice production was $46.07 billion means the subsidies were 13.6% of the total value of production as against the de minimis level of 10%.

Needs to recalibrate:

- India’s procurement for rice and wheat, even if it violates the de minimis limit, will enjoy legal immunity.

- However, India will not be able to employ the peace clause to defend procuring those crops that are not part of the food security programme (such as cotton, groundnut, sunflower seed).

- Even if the AoA is amended to exclude MSP-backed procurement for food security purposes from the AMS, procurement for other crops at prices higher than the fixed ERP would be considered trade-distorting and thus subject to the de minimis limit.

- Therefore, India needs to recalibrate its agricultural support programmes to make use of the flexibilities available in the AoA.

Provide income based support:

- India has regularly called for correcting historical inequalities like the AMS, which allows a group of developed countries to heavily subsidise their agricultural sector while unfairly targeting relatively smaller subsidies granted by developing countries.

- A more effective and lasting way of ensuring food and livelihood security of the most vulnerable and promoting sustainable agriculture trade would be by agreeing to eliminate the historic asymmetries in AMS entitlements in the Agreement on Agriculture and addressing growing hunger through effective food security programmes

- However, domestically India can move away from price-based support in the form of MSP to income-based support, which will not be trade-distorting under the AoA provided the income support is not linked to production.

Conclusion:

- The Government needs to engage with the farmers and create an affable environment to convince them of other effective policy interventions, beyond MSP, that are fiscally prudent and WTO compatible.

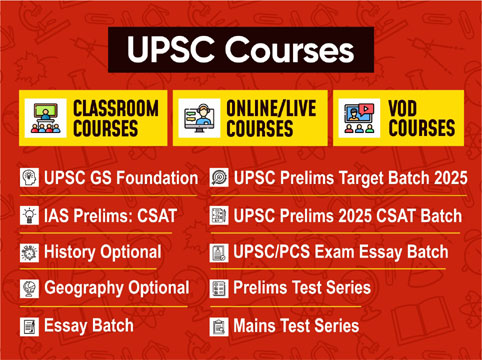

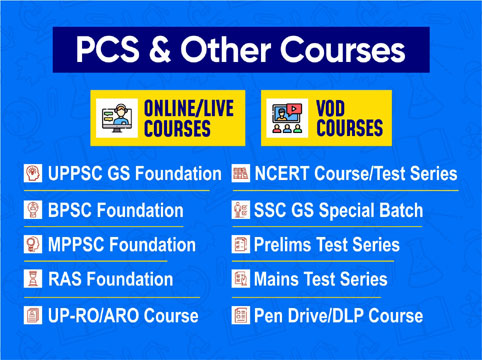

Contact Us

Contact Us  New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757

New Batch : 9555124124/ 7428085757  Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757

Tech Support : 9555124124/ 7428085757